Flying in Icing Conditions and Useful Flight Planning Icing Reports

Introduction

Ice is one of a pilot’s most insidious enemies. Rocketroute can help a pilot be more informed about the risk of icing along a particular route. Within RocketRoute, create a flight plan anywhere in the world and receive a detailed briefing pack with 3 useful reports to help assess the likelihood of icing.

This article provides an introduction to icing and the flight planning reports available from RocketRoute. Pilots can sign up for free to use RocketRoute.

The Risks of Icing

Aircraft icing is the major weather hazard of aviation. Ice can destroy the smooth flow of air, accumulate on every exposed frontal surface of the airplane, and impair the aircraft engine’s performance. There exist no hard rules on how to avoid ice since every case related to the issue is unique. All aircraft react differently on the same ice conditions. This article will help you open the door to more safety options and give you the tools to successfully avoid ice and exit a hazardous icing encounter.

In severe conditions, a light aircraft may be iced up so much that it will be impossible to continue the flight. Therefore, general aviation pilots have a huge responsibility for gathering, analyzing, and applying information to make decisions immediately. These decisions should be based on prevailing weather conditions and aircraft capability. Even a small amount of ice can significantly degrade the aircraft’s performance, increase drag, and reduce maximum lift. It can lead to an increased angle of attack and allows the underside of the wings and fuselage to accumulate additional ice. In this case, exit the icing conditions as soon as possible, keep the aircraft flying, and do not stall.

How to Avoid Icing

To avoid ice, the pilot ought to check potential ice conditions before the flight. They exist when the temperature is in the freezing range (+2°C to -20°C) and there is visible moisture or precipitation. In order to find out where there is an ice zone and where it is safe, pilots need to focus on obtaining ceiling, cloud tops, freezing levels, PIREPs, and any frontal activity over the entire route. Regardless of the type of aircraft, the pilot’s “go” and “no-go” decisions should be based on the number of reliable outs along the entire route.

Remember, even small amounts of ice can significantly degrade your aircraft’s performance and handling. An iced wing will always stall sooner and at a lower angle of attack (AOA) or a higher airspeed than a clean wing.

That is why it is very important to remove all snow, ice, and frost from the aircraft during pre-flight. Be sure to check during pre-flight that the pilot heat is working.

If you are piloting a protected air-craft remember to check your ice protection systems during run-up.

The best insurance against an icing encounter is AVOIDANCE.

To avoid an icing encounter:

- develop a pre-flight plan;

- know where the ice is;

- know where it is safe.

Pay close attention to the Outside Air Temperature (OAT) gauge. In-flight icing conditions exist when:

- there is visible moisture (including clouds, rainbows, and precipitation);

- outside air temperatures are in the freezing range (+2° C to -20° C).

Icing conditions do NOT exist:

- outside the clouds;

- if there are NO freezing precipitation;

- temperatures are OUTSIDE the freezing range (unless freezing rain falls from higher altitudes).

To know where is the ice and where it is safe, a pilot needs to obtain the following info:

- ceilings;

- cloud tops;

- freezing level;

- PIREPs (pilot reports);

- frontal activity along the route and up the weather.

Be sure always to build reliable outs in your flight plan. You may have to re-route to ensure this.

If reliable outs are NOT possible, consider DELAYING or NOT-GOING.

Types of Ice

It is important to know that there are three types of ice: rime, clear (or glaze), and mixed.

Clear ice forms when supercooled water droplets strike the surface, but do not freeze instantly. This type of ice is hard and heavy. It is difficult to remove it by applying the deicing system.

Rime ice is formed by small drops, which are similar to drops within light drizzle or stratified clouds. Freezing of the liquid happens extremely fast, even before drops expand over the surface of the aircraft. This type of ice is less weighty as compared to clear ice, but it has an irregular shape and its surface is rough. As a result, it is able to decrease airfoils’ aerodynamic efficiency.

Mixed ice appears rapidly if liquid drops are of different sizes or they are mixed with particles of snow or ice.

Whether you are exposed to light, moderate, or severe ice, this determines how the aircraft responds to the icing environment. This process involves a combination of ice-protecting systems, aircraft configuration, as well as flight and atmosphere conditions. Light ice indicates that the rate of accumulation is such that occasional use of ice protection systems is required to remove or prevent accumulation (every 15-60 minutes). Moderate ice shows that frequent ice-protecting systems are necessary to remove or prevent ice (each 5-15 minutes). Severe ice demonstrates that the rate of ice accumulation is so fast that ice-protection systems fail to remove it (de-ice boots are overwhelmed and the pilot needs to exit this condition immediately). There is also a weather phenomenon called supercooled large droplet or SLP. For general aviation aircraft, SLP conditions should be considered severe and extremely dangerous.

Actions to Take When in Icing Conditions

If icing conditions DO EXIST be vigilant to the cues of ice accretion:

- Pay attention to the areas of the aircraft with a small radius or thin leading edge. They will accrete ice first.

- Handfly your aircraft in possible icing conditions. This will provide tactile cues to early signs of potential roll or pitch upset.

- monitor your airspeed and the power settings. If you notice significant performance degradation, EXIT the conditions IMMEDIATELY.

It is always a good idea to work to exit icing conditions, whether the aircraft is protected or not, and never use the ice-protection system as a tool of complacency.

Ice protection systems are best used as a defensive measure to buy time until you can exit the icing conditions. Don’t assume that you are legal to fly in icing conditions because your aircraft has a supplemental type certificate (STC) for an optional ice protection system.

An STC system indicates the hardware is airworthy, but its effectiveness in ice removal may NOT have been demonstrated. Only with certified ice protection systems can you intentionally fly into known or forecast icing. If you are not sure, check the Pilot’s operating handbook.

Kurt Blankenship, NASA Icing Research Pilot, says, “If you are in icing, especially during the approach - hand fly your aircraft. Your autopilot is likely to miss the first indications of an upset. If you hand fly you feel the impending handling and you will be able to recover before it is too late. Even if your aircraft is protected, you are going to continually build ice. Hand fly the aircraft.”

5 Safety Outlets

There are typically 5 safety outlets and a priority handling device in any in-flight icing situation. Pilots can climb, descend, continue, divert, and return. These safety outlets are applied both to protect an unprotected aircraft whose safe outcome is in question. The priority handling device is the ability to declare an emergency, which gives a pilot priority handling and allows for addressing the situation as soon as possible. Climbing should be considered when the aircraft is capable of reaching the top of the clouds. Even when remaining in clouds in the climb, colder temperatures can sometimes be reached reducing icing probability. The pilot should check with ATC for pilot reports on where the top of the clouds can be reached. Descending can be used when the pilot gets below the clouds or to temperatures above freezing. However, it should be mentioned that it is never allowed to remain in the freezing rain or drizzle. Continuation of a flight is possible if the pilot is in the process of exiting the cloud. When realizing that the weather conditions are worse than expected, it is better to return to the departure airport. Diverting should be considered where a possibility to divert and land at an alternate airport is available. Any course change requires communication with ATC, where the level of urgency should be conveyed. Declaring an emergency will give you priority handling. By doing so, ATC is allowed to help you exit the icing conditions as soon as possible. Recall that Federal Aviation Regulation 91.3 states: “In an in-flight emergency requiring immediate action, the pilot in command may deviate from any rule of this part to the extent required to meet that emergency.”

If iced, be careful of configuration or flight condition changes. Ice that seems to have little effect during the cruise can have significant effects when the airspeed is reduced or the configuration has changed. Especially during approach or landing your aircraft is pushed towards its performance limits. This puts it in some risk for an ice-contaminated wing or tail stall.

Recovery From Ice-contaminated Wing Stall

Ice-contaminated wing stall occurs when the wing angle of attack is too high. This corresponds to a slow speed. If a wing does stall, the aircraft will either roll or pitch its nose down.

The Recovery from an ice-contaminated wing stall is the same as a clearwing stall:

- Immediately reduce the wing angle of attack.

It can be reduced by pushing forward on the yoke and adding power.

On approach:

- keep your speed up. This will increase your wing stall margin;

- consider a no flap or reduced flap landing. This will increase your tail stall margin;

- if you are unable to maintain altitude, consider delaying gear extension until the runway is assured.

Remember, keeping the aircraft flying and under your control is paramount to survival.

In conclusion, it is necessary to say that the best insurance against icing is its avoidance. A pilot must develop a pre-flight plan to know where the ice is and where is it safe (ice can only exist where there is visible moisture and temperatures are in a freezing range). Is it important to be sure that the pilot is aware of freezing levels, can tops, ceilings, and any relevant PIREPs. Information regarding any frontal activity along the route and up weather is also significant. Reliable outs in the flight plan ought to be built, and if those are not possible, delaying of a flight can be considered. General aviation pilots should report and request PIREPs since they are the most accurate way of determining icing conditions. Whether the aircraft is ice-protected or not, the ice protection system should never be used as a tool of complacency. Typically the pilot can climb, descend, continue, divert, return, or declare an emergency. When approaching, speed should be kept up (this will increase the wing stall margin). Also, a no flap or reduced flap approach and landing can be considered to increase the tail stall margin. All these tools are to be remembered since they are a key to avoiding ice troubles.

Using RocketRoute to Assess Icing Risk

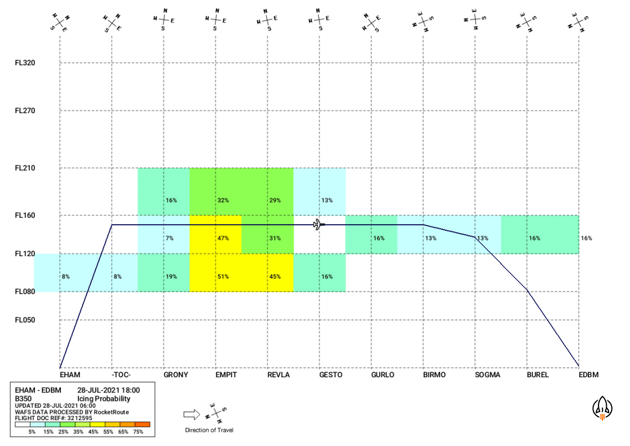

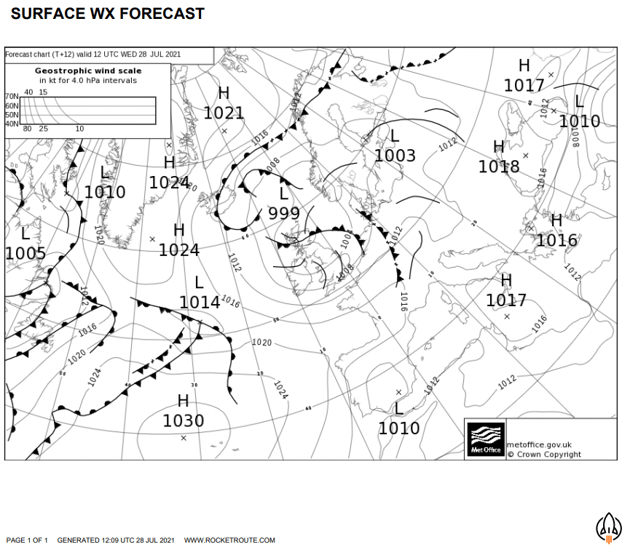

Using the Rocketroute system can help you in assessing the risk of icing during your flight. The system generates three reports that give you detailed information regarding icing conditions (see below Significant Weather Report, Icing Vertical and Icing Horizontal Reports). These reports are included in breifing pack and are automatically updated every 1 hour using a forward 5 day weather forecast.

Support

Our ‘support mode’ is always on, feel free to reach out to our Sales team to ask your questions.

You may also want to explore our free webinars highlighting the most popular features on our YouTube channel.

New to RocketRoute? Join us today and get a 14-day free trial or become a RocketRoute member to enjoy all the benefits of seamless flight planning.